Innovations throughout history have often been pioneered by the military before finding a civilian application, but Vendigital’s Paul Adams identifies three important areas where defence can learn from commerce, as defence features writer Peter Jackson reports.

Revolutionary changes in the commercial and manufacturing worlds could also transform defence procurement.

This is the view of Paul Adams, Head of Aerospace and Defence with procurement and supply chain specialists Vendigital, who identifies three areas where developments in the commercial sector are likely to transform defence.

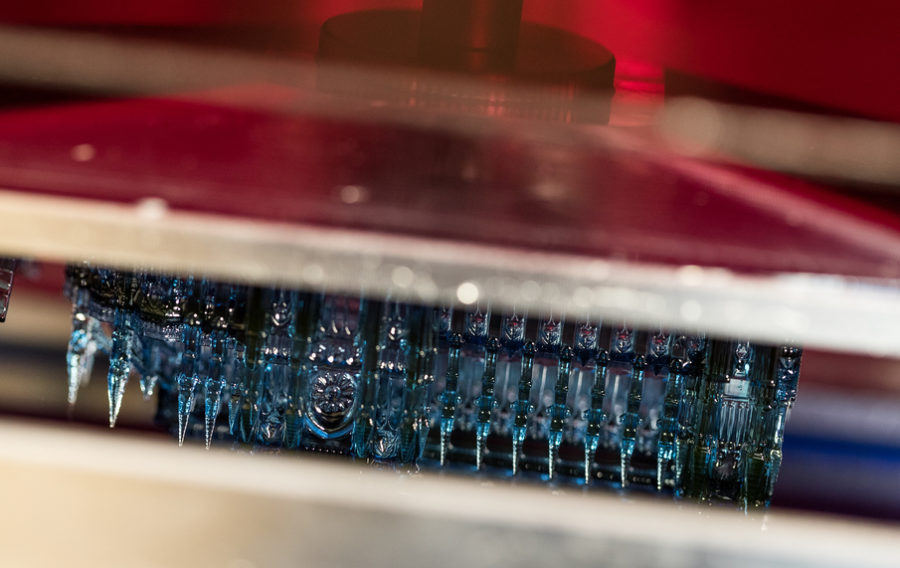

First is 3D printing – or, as it is more accurately called, additive manufacturing – the processes by which layers of material are formed under computer control to create a three-dimensional object.

Currently additive manufacturing is being used to make parts predominantly from plastic but it is also beginning to be used for metal components.

“General Electric are really pushing hard with it in the aero engine supply chain,” says Adams. “Rolls-Royce are also looking at options to introduce 3D printing for parts for the lift fan for the short take-off version of the Joint Strike Fighter.”

However, he argues that the manufacturing technology must be further enhanced before the full potential of additive manufacturing can be realised in defence.

“The first thing is the speed of manufacture,” he notes. “People say let’s get rid of the whole supply chain and stick a 3D printer in an aircraft hangar and we’ll be able to print spare parts, which sounds wonderful, but we are not there today. However, as the speed of the machinery increases, that is a realistic prospect in the future.”

If this aircraft hangar were to be supplied with metallic powder and other manufacturing consumables that vision could be close to realisation.

He adds: “The limiting factor today is the practicality of the speed with which machines produce parts, but as the speed of the machines increases that will become more and more attractive.”

The second key step for additive manufacturing to come into its own in the defence industry is for designers to realise just how much of a game-changer it could be and not to look at additive manufacturing in terms of another means of doing what has been done in the past, but as a way of enabling them to do entirely new things.

Adams explains: “Additive manufacturing is such a new and novel technology, design engineers in most of the big organisations don’t really understand the capability of the process both in terms of material properties but also fundamentally in terms of what types of parts you can produce with this technology.

“The best way to describe it is that at the moment we take a block of metal and we knock chunks out of it until it becomes a certain shape. Effectively, what additive manufacturing allows is to grow the way plants grow, molecule by molecule. You can create some incredible shapes which look nothing like what we would typically see in an aircraft today but are optimised for strength and weight across the different molecules within that structure.

“GKN have been looking at 3D printing technology for Airbus and they talk about components that have the same, or better, strength properties for half the weight compared to a standard manufactured product.”

Adams believes that once these two pieces of the jigsaw – improved 3D printing technology and greater design awareness – are in place, then manufacturing and the defence procurement supply chain will be revolutionised.

He points out some of the implications of armed forces being able to ’print’ spare parts.

“There are plenty of examples where armed forces operate in places where there is nothing or where they have to set up very quickly. Rather than having to set up a whole logistics supply chain, if they could, for example, stick a 3D printer on the back of a Hercules and drop it in a war zone that would be transformational.”

A second development which is likely to have enormous impact on defence in general and aerospace in particular is the development of autonomous vehicles.

Attention has been concentrated on self-driven cars or drones but Adams is interested in the logistics perspective and opportunities in the military supply chain. He points to a large-scale trial scheduled for next year around the Korean peninsula for autonomous shipping.

He says: “Moving significant amounts of ordnance or vehicles becomes an entirely different prospect if done autonomously at sea.”

Similarly in the air, while drone-based delivery is widely discussed in a commercial context, it could also be a valuable means of supply for forces in-theatre.

“Today, if a force needs supply, they have to call in a helicopter and you need the right people – including the pilots – in the right place. However, applying commercially available technology to do that with drone-based delivery not only takes a huge amount of risk away, it also allows you to respond much more quickly because you are not people-dependent.”

He also argues that as drones are much cheaper than helicopters, supplying large amounts could be done more effectively.

“Acting in really remote parts of the world, there have been some trials done on launching drones from moving vehicles such as transport planes,” he says. “That, again, gives you an entirely different capability; you have the long-range blunt instrument of taking something somewhere on an aircraft and then the precise level of detailed delivery that a drone could provide.”

He argues that the benefits of drone supply would not only be in terms of responsiveness and flexibility but also in terms of cost.

“The only question really is around trusting the technology. We’ve clearly got there in terms of autonomous vehicles in the air. Reaper drones are flown by a person for a certain amount of their mission but a lot of it is done automatically using artificial intelligence. It’s a case of how you transition that into a more wide-scale application.”

The third area of commercial and industrial innovation he believes could have a beneficial impact on defence procurement is in the field of cost benchmarking.

“There’s a lot the military can learn from industry in the way in which it understands what things cost and how it uses that information to get the best deal from its supply chain,” he says.

Government uses a variety of tools such as cost engineering and has the Cost Assurance and Analysis Service, CAAS, but he believes it should use benchmarking to look at industry for a better idea of what it could pay.

He explains: “So, if you need to buy 100 desks’ worth of office space, for example, this is how much it costs the MOD to do that; but how much does it cost a printing company to do that? How much does it cost a manufacturing organisation to do that? Draw those parallels and then understand why and where you’re paying more than you should be and use that data to better negotiate with your supply chain.

“You can take this approach on a much broader scale. For example, if you look at a fleet of military vehicles, it would be very easy to benchmark the costs that the UK military are paying to run those vehicles and draw parallels with what industry are paying, and use that data to get better bang for the buck.”

If Adams is right, in terms of technology and processes, those engaged in defence procurement can learn valuable lessons from their civilian counterparts.

If you would like to join our community and read more articles like this then please click here