The UK Metamaterials Network is accelerating research to find innovative metamaterials for a variety of applications in the defence industry. But what are these exciting new materials capable of? This article from Withers & Rogers explores.

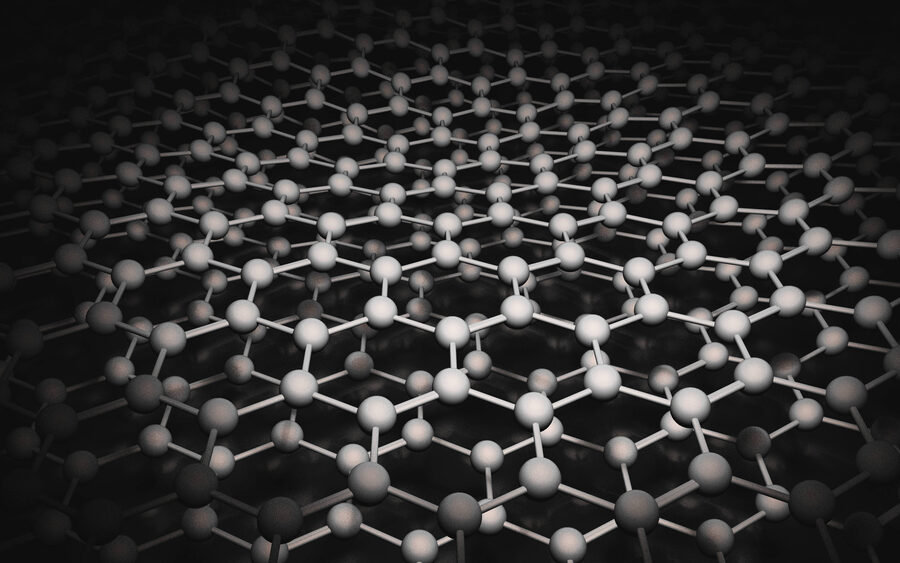

Metamaterials are nanoscale structures that don’t exist in the natural world. They are typically made from two or more known materials such as plastics, metals, organic matter, solids or liquids. They are developed for the unusual or unexpected properties they have, which derive from their novel structure rather than the materials from which they are made.

Set up with the aim of establishing a world-class metamaterials-enabled UK ecosystem, the UK Metamaterials Network (UKMMN) has awarded numerous grants to university-led R&D programmes across the UK since being founded in 2021. The network has recently published a series of roadmaps reflecting on six special interest areas, including one for Microwave and Wireless Metamaterials, which is aiming to address practical challenges linked to defence and other industry applications.

One of the main areas of focus for engineers targeting defence industry applications is the protection of people and objects. For example, a team of scientists at Florida University have patented a unique metamaterial (US 11011834 B2) made from dielectric material, which can withstand high temperature, high pressure and/or radioactive environments, and still enable transmission of radio waves through the material with low losses. A further patent has recently been granted to the same research team for a novel radome structure that uses the new metamaterial.

Another novel metamaterial that could be used to protect people and objects is a patented technology that acts like a ‘radiation shield’ when using mobile devices. Patented in Europe by research scientists at UK company Sargard Limited, the protective shield (EP 3 631 896 B1) has a negative refractive index in the frequency band at which the device is emitting radiation. As such, it is able to protect the user from the potentially harmful effects of electromagnetic radiation, without impacting the reliability of radio transmissions.

Another key objective in the search for metamaterials for defence is ‘impact protection’. Research scientists at the University of Washington have secured patent protection in the US (US 11,028,895 B2) for a metamaterial with advanced shock-absorption and impact mitigation properties. Formed from triangulated cylindrical origami unit cells, which are capable of twisting and compressing in response to impact forces, resulting in the generation of unexpected wave propagation behaviour through the metamaterial.

In a fast-developing area of scientific research it is difficult to pinpoint innovation trends, however, it makes sense for scientists to reference all potential areas of purpose in their patent applications. One example of a metamaterial with potential applications in different industries is a new polar metamaterial which has been developed by scientists at the University of Missouri, and is covered by pending patent application US 2022/412422 A1. The material has a unique lattice-like structure and can act as a cloak for elastic waves. Such a material could help buildings to withstand the multidirectional waves generated during earthquakes and provide flexible protection to soldiers and equipment from blast energy.

With global patent filings linked to the structural composition of metamaterials or their application R&D rising year on year, it is important for innovators to consider their IP strategy carefully. Some defence applications may not be suitable for publication for national security reasons, in which case, security provisions can be utilised. In other cases however, innovations should be patented to leverage their commercial potential.

With much metamaterials R&D at an early stage, there is a higher risk of inadvertent or early disclosu

re, which could jeopardise an innovation’s patentability in the future. Clear intellectual property (IP) advice should be given to research scientists at the outset, and R&D teams should ensure they have agreements in place to protect any pre-existing or collaborative IP rights before entering into research-led partnerships.

Gemma McGeough, partner, and Chris Hunter, senior associate, are both patent attorneys at European IP firm, Withers & Rogers. They specialise in advising innovators developing engineering materials for a variety of industry applications.